In his more recent projects, Tom Stuart-Smith takes an experimental, naturalist approach to horticulture, as seen in the landscape at a vineyard in Spain’s Duero Valley. Photo by Andrea Jones

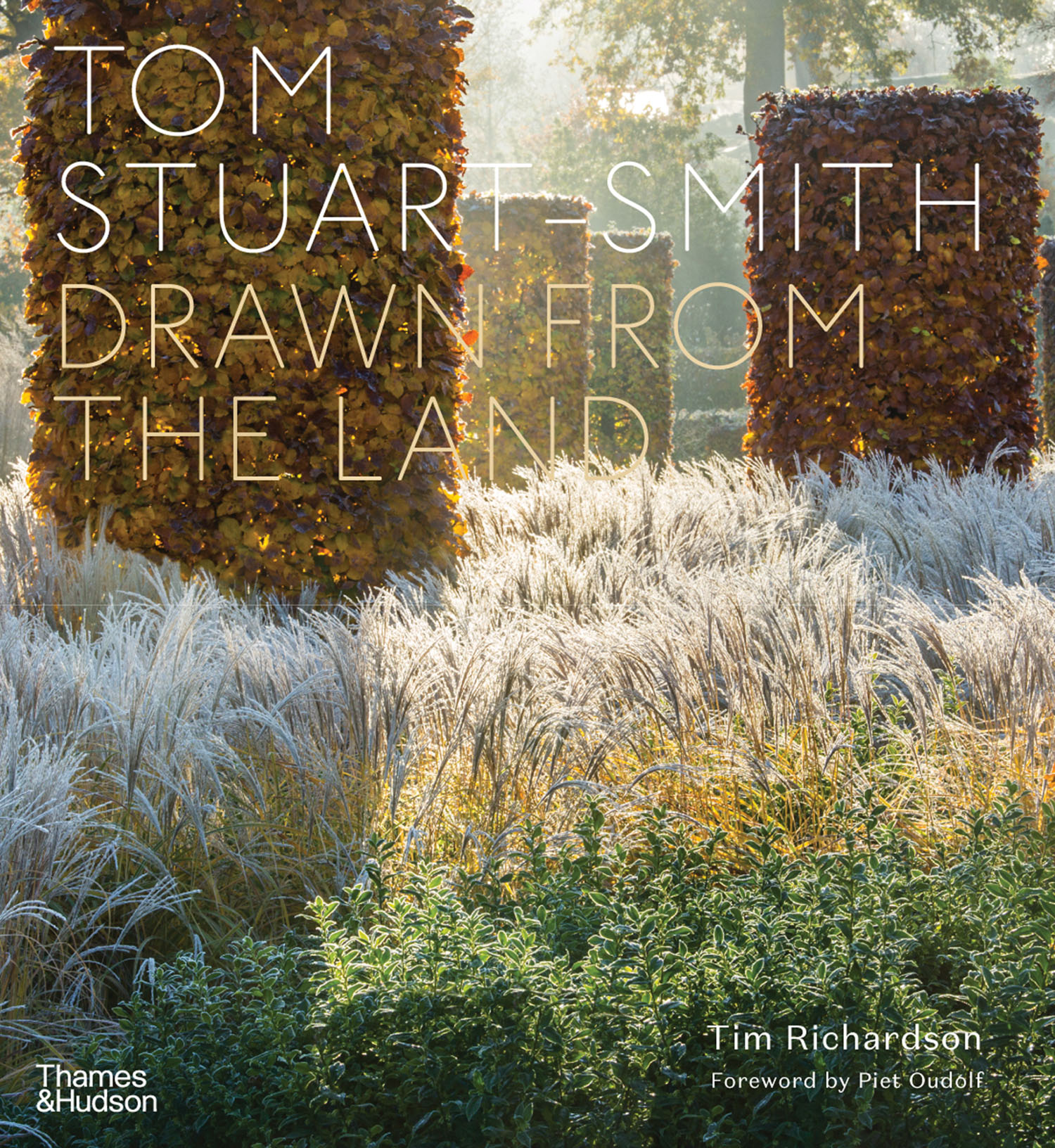

Tom Stuart-Smith: Drawn from the Land (Thames & Hudson, 2021)

I saw the Bury Court meadow, which is actually quite a modest area, in its prime, before the Deschampsia died out and the clover went rather leggy. It had such simple grace, as if it were just getting on with its own business of being grass and clover. Growing, flowering, and of course dying. Piet is the evangelist of decay.

At his own home in the Hertfordshire countryside, Tom designed a courtyard around steel water tanks he had previously used in a 2005 Chelsea Flower Show garden. Photo by Andrew Lawson

Tom collaborated with horticultural ecologist James Hitchmough to create the meadows at Oakhill in Kent, England. Photo by Allan Pollok-Morris

As I developed my own practice I was able to expand my garden at home, and my experimentations with plants accelerated. The garden began to take some shape, and various patterns started to fall into place about how I was using plants.

I moved away from the idea of having very different types of planting in different areas of the garden, which I think I had inherited from all those Arts and Crafts gardens I had visited. This seemed more a collector’s approach than one in which planting is a tool to create and manipulate the atmosphere of a place. Instead I gravitated towards the concept that planting is like a medium that can flow between spaces, gradually being transformed by them to take on a character that emphasizes the physical setting or the desired mood in relation to the nature of the surroundings. So there might be a subtle gradient of change between different parts of a garden, but not sudden discontinuities.

LANDSCAPES BY TOM STUART-SMITH

Excerpted from Tom Stuart-Smith: Drawn from the Land © 2021 Thames & Hudson Ltd., London; text © 2021 Tom Stuart-Smith. Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc., thamesandhudsonusa.com.