In the New Orleans home of Jennifer Heebe, designer Gerrie Bremermann used an Oriental rug in subtle hues to tie together an elegant dining room. Learn to identify rug patterns and floral rug motifs in our guide at the end of this story. Photo by George Long

Lushly patterned rugs are part of Shadi Shafiei’s earliest childhood memories. Growing up in Iran, she and her sister played on their parents’ Persian carpet, crawling over what they imagined to be brown mountain ranges and swimming through blue and green rivers. Now as an art historian working at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), she is still fascinated by these intricately knotted works. When LACMA unrolled its palatial, jewel-toned Ardabil Carpet for an exhibit in 2017, Shafiei was mesmerized.

“Awestruck, I walked around this magnificent carpet, deeply absorbed in the elaborate vegetative and floral patterns covering the rug,” she wrote on social media. “It felt as if I was walking through one of Iran’s traditional, lush gardens with a geometric pool in the center.”

Rarely exhibited because of its size and sensitivity to light, LACMA’s Ardabil Carpet has a sister carpet at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Representing a golden age in Safavid dynasty weaving, they are among the world’s most exceptional textiles. Ardabil Carpet, Iran, dated 1539–40, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of J. Paul Getty, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The carpet’s representation of a pool, a nod to the significance of water in Persian gardens, along with the flourishing botanical life, suggests a place of physical and spiritual refreshment. In short, paradise. Whether palatial or modest in scale, myriad Oriental rugs abound with Islamic garden imagery.

“The rug is an antique Oushak. My client had it in another house, and it was decided that it would be perfect for her New York apartment,” says designer Amelia Handegan. “Rugs like this are a favorite way of adding color and pattern.” Photo by Pieter Estersohn

One rug pattern known as chahar bagh (Persian for quartered garden), shows an aerial view of an enclosed Persian garden. Looking down onto such a rug, one can typically spy dividing bands that represent channels of water as well as rectangular flower beds bordered by trees and more flora. During the summer of 2018, the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibited a spectacular and rare variation of the classic chahar bagh style, the Wagner Garden Carpet, a 17th-century masterpiece woven in Kirman, Iran, and now owned by Scotland’s Burrell Collection.

“It buzzes with life,” writes Sheila Canby, Metropolitan Museum of Art curator in charge of Islamic art. Mirroring a formal walled garden, the Wagner depicts eternal springtime and includes what Canby describes as a dizzying mix of multicolored butterflies and moths, birds, animals, flowers, leafy trees, and gleaming water. It’s this sense of abundance that suggests “a delightful, perfumed bower,” she explains.

For a home in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, designer Richard Keith Langham included an antique Persian Sultanabad carpet. Photo by Trel Brock

Other designs may be less literal interpretations of a complete garden but still contain profuse floral elements. Weavers may simplify or artfully exaggerate blooms for poetic effect. Clinical depiction of flowers isn’t their motive. But there are iconic floral motifs to know.

“These motifs can be large or small and found in many different types of rugs,” says Paige Albright of Paige Albright Orientals in Birmingham, Alabama, who provided the rugs for the 2021 Flower Showhouse. “What I find interesting is how the old motifs are also used in modern carpets, often stylized and over-scaled to create a new version rooted in tradition.”

“The colors all meld together for a classically chic look, then and now,” says designer James Farmer of the circa 1900 Turkish Oushak he chose for this space. Photo by Emily Followill

RUG PATTERN PRIMER: FLORAL MOTIFS

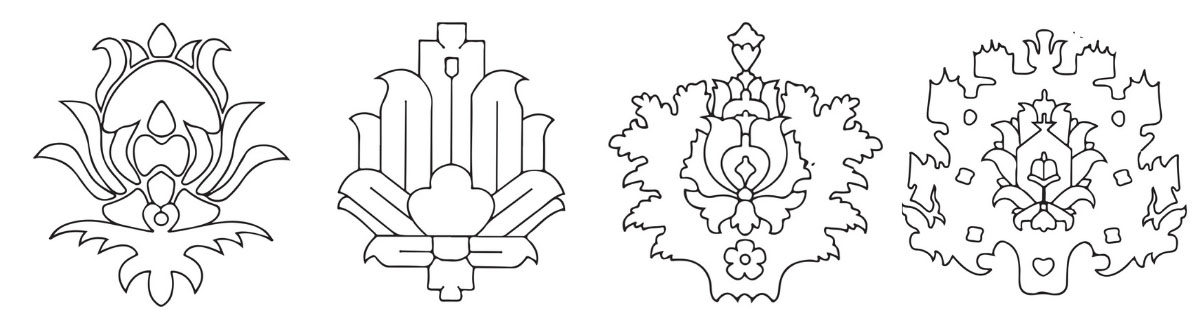

ROSETTE

“A rosette is a horizontal cross section of a flower,” notes Albright. Imagine a circular form viewed from above. Fun fact: “When a rosette is surrounded by serrated leaves, it becomes a crab motif,” she adds.

PALMETTE

“One of the easiest ways for me to identify floral motifs in a rug pattern is to visualize a flower and recall biology class. A palmette is the vertical cross section of a flower and has a fan-like shape,” explains Albright. According to Peter F. Stone’s book Oriental Rugs, the palmette is based on the lotus flower and its spread petals and is interpreted by weavers in numerous ways.

—

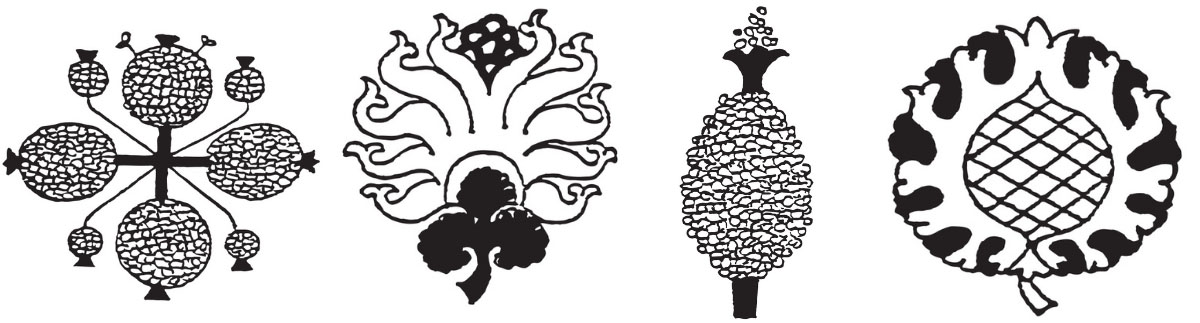

POMEGRANATE

A symbol of fertility, the pomegranate tree is common to rugs of Eastern Turkestan, but abstractions of the fruit also appear in Mughal and Chinese carpets, writes Stone.

—

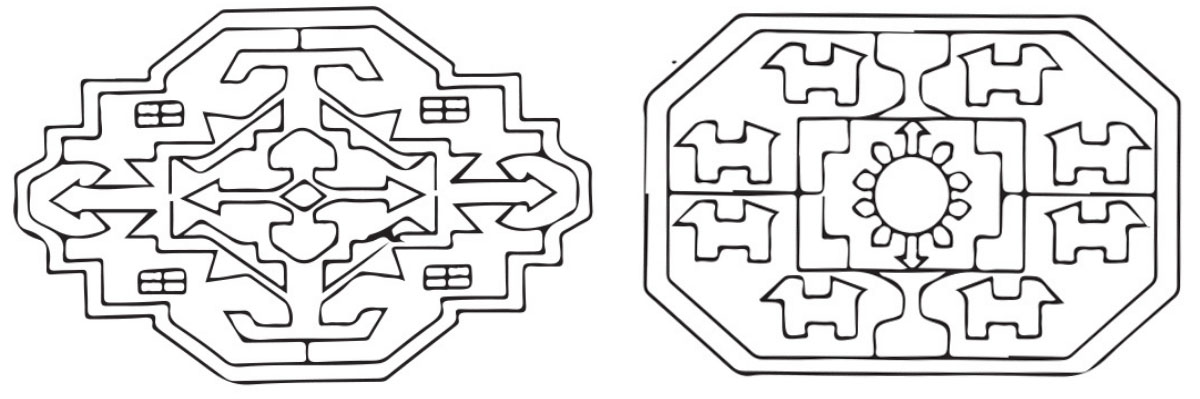

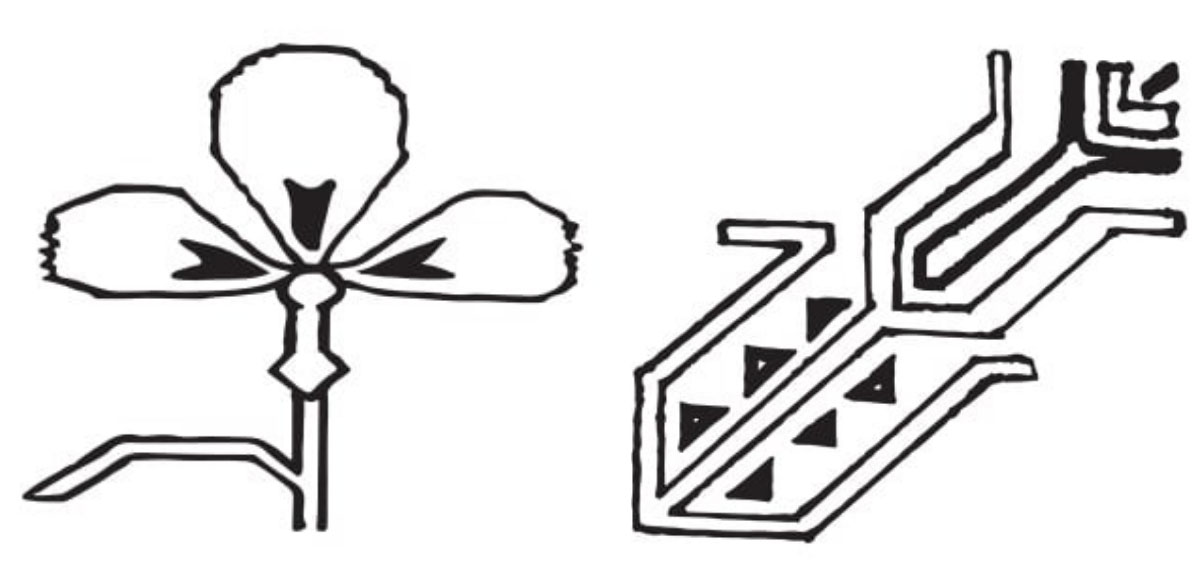

GUL

Persian for flower, this motif is octagonal or angular and associated with tribal emblems. According to Stone, the gul is usually repeated to form an allover pattern.

—

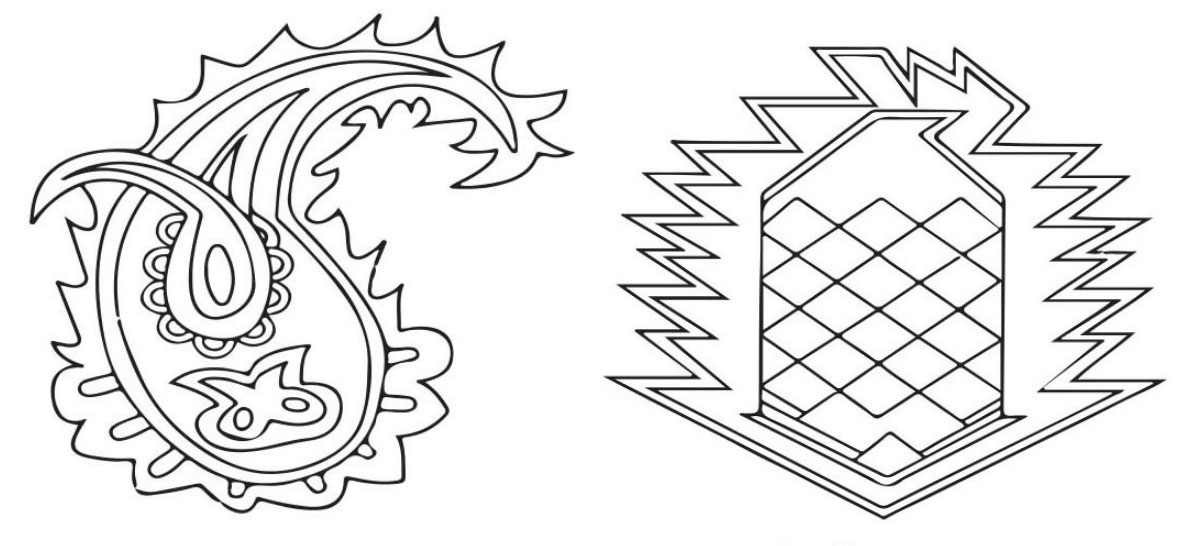

BOTEH

A leaflike shape or stylized teardrop that became known as paisley in the West. Persian for bush or cluster of leaves, boteh may be highly detailed or simple, and the motif often appears in the field of a rug, forming an overall pattern.

—

OTTOMAN

A fan-shaped carnation (left) and a stylized, almost geometric interpretation of a tulip (right) are depicted from the side to emphasize the blossoms’ unmistakable profiles.

—

LOTUS

A Buddhist symbol of purity, the lotus is associated with Chinese rugs but is used cross-culturally. It may also suggest summer, fruitfulness, and happiness.

—

ARABESQUE

A tendril-like vegetal ornament used in Islamic art, this motif typically incorporates leaves or blossoms. Split-leaf styles are known as rumi.

—

MUGHAL-STYLE

A more naturalistic but still poetic depiction of flowering plants, like poppies and cockscomb, often shown in profile and arranged in rows. Influences include European botanical drawings and Indian and Persian art.

By Courtney Barnes

This story originally appeared in Flower magazine’s November/December 2018 issue. Subscribe or find the current issue of Flower in a store near you.