Local sights, such as mountains in the distance, colloquial phrases, or even news headlines can serve as a jumping-of point for Patrick Dougherty’s works such as Close Ties for the Scottish Basketmakers’ Circle in Dingwall, Scotland. Photo by Fin Macrae

Patrick Dougherty peers out from a swirl of artfully entwined branches in a piece called Ruaille Buaille (2008) at Sculpture in the Parklands, County Offlay, Ireland. Photo by James Farher

Video: Watch Patrick Dougherty create a work at the Peabody Essex Museum.

“My grandmother was a farmer and artist in Oklahoma, guided mostly by her instinct and imagination because she had no real exposure to other artists, and my mother gave us the ability to use our own imaginations. She encouraged us not to feel constrained,” says sculptor Patrick Dougherty, pausing briefly to discuss his creative roots while braving a bitterly cold February morning as he works outdoors on location at Durham, North Carolina’s Museum of Life and Science.

Assisted by a team of volunteers, the installation he is building with found branches and saplings will be comprised of massive, bush-like spheres inspired in part by the museum’s existing hedges. “For many children now, their first experience with nature involves suburban bushes, so I think these forms will resonate with the young visitors. But my rounded shapes will be somewhat zany, appearing to spin,” adds Dougherty.

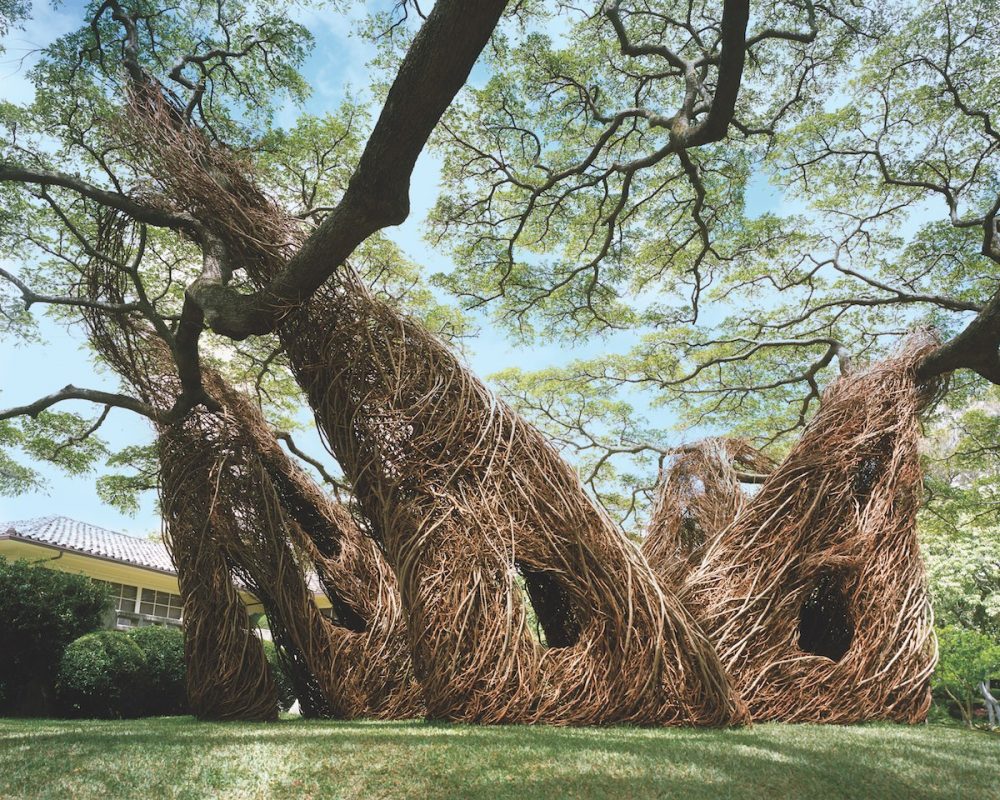

Patrick Dougherty used oleander, java plum, ironwood, eucalyptus, and bamboo branches in Birthday Palace (2014), designed to commemorate the 50th jubilee of the National Tropical Botanical Garden in Hawaii. Photo courtesy of the National Tropical Botanical Garden

This sense of movement characterizes most of the North Carolina–based sculptor’s organic installations, which have sprung up in public spaces from Seoul, Korea, to Savannah, Georgia, and which feel at once contemporary and primordial. Described as stickwork, the large-scale pieces are essentially constructed through a process of layering. Dougherty weaves one stick through another a bit like a bird building a nest. After the central framework is in place, the artist begins to add gestural lines. He says that by positioning all of the smaller ends of his sticks in one direction he is able to convey a whirling, windblown sensation.

Installations such as Little Ballroom (2012), Federation Square, Melbourne, Australia, encourage as much interaction as possible with visitors by design. Photo by Meagan Cullen

Interaction is also a key component. Most of Dougherty’s works have open passageways that allow visitors—and sometimes tropical trade winds—to literally get inside the art, whether the structure is his woody labyrinth divided into 16 rooms at the castle in Nantes, France, or Birthday Palace, a folly at Hawaii’s National Tropical Botanical Garden, designed with round windows and an oculus in its dome. And community collaboration is integral to his process as well. Often the sculptor’s commissions come from botanical gardens, museums, and universities (although he did once swathe the exterior of the Max Azria boutique in Los Angeles). After he arrives at the site of his latest project, the sponsoring institution typically introduces him to a band of enthusiastic volunteers, and then Dougherty sets about gathering local branches, which could be detritus from a well-maintained property or saplings rescued right before bulldozers plow land undergoing development.

Na Hale ’Eo Waiawi (2003) at the Contemporary Museum in Honolulu is comprised of regional strawberry guava and rose apple saplings. The form complements the swaying lines of the site’s existing monkeypod tree and suggests island breezes. Photo by Paul Kodama

“I never really know exactly how many volunteers I will have or what our materials will be—or, for example, what sort of scafolding will be at our disposal. But being able to adapt and collaborate is part of the process,” says Dougherty. Working full-on in public view, answering questions from passersby, and graciously listening to their opinions and stories seems to come with the territory, too. In fact, the artist appears to actually draw energy from his conversations with the spectators.

While Dougherty provides his clients with preliminary drawings, he finds that the various institutions that approach him happily allow for some flexibility. Rigid adherence to a master drawing could inhibit some of the magic that occurs once he and the team start working with their natural materials—dogwood, elm, maple, and sweet gum, and occasionally sassafras, crabapple, and bamboo—that don’t always bend or fill a space as expected. Staying open to and in tune with the location yields better results, he says.

Although many of Dougherty’s designs resemble dwellings of various kinds, his perspective aligns with the work of a gardener as much as an architect because his creations are not intended to be permanent. After about two years, his installations usually start to fade and will ultimately disintegrate. The idea is that their ephemeral nature makes the pieces all the more beautiful.

The series of structures Dougherty built for his installation Just Around the Corner (2003) at New Harmony Gallery of Contemporary Art in Indiana features his signature rounded windows as well as doors for visitors. Photo by Doyle Dean

Change certainly doesn’t seem to frighten the sculptor. Most months of the year he is in a different city, perhaps even in a new hemisphere, engaging with a diverse group of people for about three weeks until the latest installation is complete. (When not out in the field, he is home with his wife and son in their own Chapel Hill, North Carolina, garden.) He turns 70 this year, and although he has tackled roughly 250 projects and received numerous affirmations, including a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and the 2011 Factor Prize for Southern Art, Dougherty is far from jaded. “I have my eye on an abbey in France and the botanic garden in Montreal,” he says. “The world is always full of opportunity.”

Watch Dougherty create a work at the Peabody Essex Museum.

By Courtney Barnes

See more of Dougherty’s work in Stickwork (Princeton Architectural Press 2010)