A circular island of mounded evergreens partially hides the arch-embraced entrance, while stained glass windows and half-timbers underscore the Tudor façade at the Krisheim estate in Philadelphia’s Chestnut Hill neighborhood.

As the country prepares to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, much of our attention focuses on the great public parks and recreational spaces he created—Central Park; the park systems in Boston and in Buffalo, New York; and roughly 100 others. In addition, the talented designer was responsible for 50 residential communities and the campuses of around 40 academic institutions. However, it was his firm’s involvement in more than 200 private estates that is most fascinating.

An island of layered evergreens studded with seasonal blooms highlights the graceful circular drive.

The iconic estate unfolds gently beyond scrolled iron gates, almost as if plucked from an English storybook.

While Biltmore, constructed in North Carolina for George Washington Vanderbilt, represents the pinnacle of Frederick’s late career, it’s the Krisheim estate, located in Chestnut Hill near Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, that constitutes one of the firm’s most elegant private projects. Although the estate’s timeline coincided with Frederick’s impending retirement, his overarching philosophy strongly influenced the design and is evident down every woodland path, around each splashing water feature, and through every sun-dappled vista.

A raised grotto-shaped enclosure of exquisitely chiseled, local Wissahickon schist provides protection for the Boy Fountain, created by Norwegian-born artist Johan Selmer-Larsen in 1912. By the pool below, a bronze of the mythological Narcissus by George Hancock admires his reflection.

Krisheim’s story began when 50 wooded acres of rolling land acquired by Henry Howard Houston were left to his daughter Gertrude after her marriage to Dr. George Woodward in 1894. Upon returning from a yearlong honeymoon, the couple hired James Frederick (Fred) Dawson, a landscape architect who subsequently joined the Olmsted firm, to plan the gardens that would frame their splendid home designed by Peabody and Stearns.

“They wanted the grounds and the home to look as if they had always been there,” says Philadelphia landscape architect Robert (Rob) J. Fleming. Plans and historical correspondence indicate the ambitious exercise took about 15 years, with the house foundations laid in 1910 and the final project completed in 1912.

Shafts of early-morning light course through the branches of an ancient red maple that appears on Fred Dawson’s original plan.

As for the gardens, Fred Dawson, who by then was a partner in the Olmsted Brothers firm, faithfully adhered to Frederick Olmsted’s love of peaceful, pastoral design. “Parts of the property are steeply pitched, while others feature broad grassy areas studded with important trees,” says Rob.

A lush border of hydrangeas lines the Annabelle Walk leading to the cool, rustic Summer House, which offers respite from Philadelphia’s summer heat.

In 1964, after serving as the beloved Woodward family home for 52 years, Krisheim was given to the Presbyterian Church. Twenty years later, the Woodwards’ youngest son, Charles Henry, bought it back and refitted the top two floors into nine apartments. But it was the Woodwards’ grandson, Charles (Chuck) Woodward, who resolved to return the estate to its former glory. Determined to remain true to the land’s original intent, he hired Rob to oversee the garden restoration, and the two men pilgrimaged to the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline, Massachusetts, to study relevant documents. Propelled by their discoveries, the duo began the project in 1989.

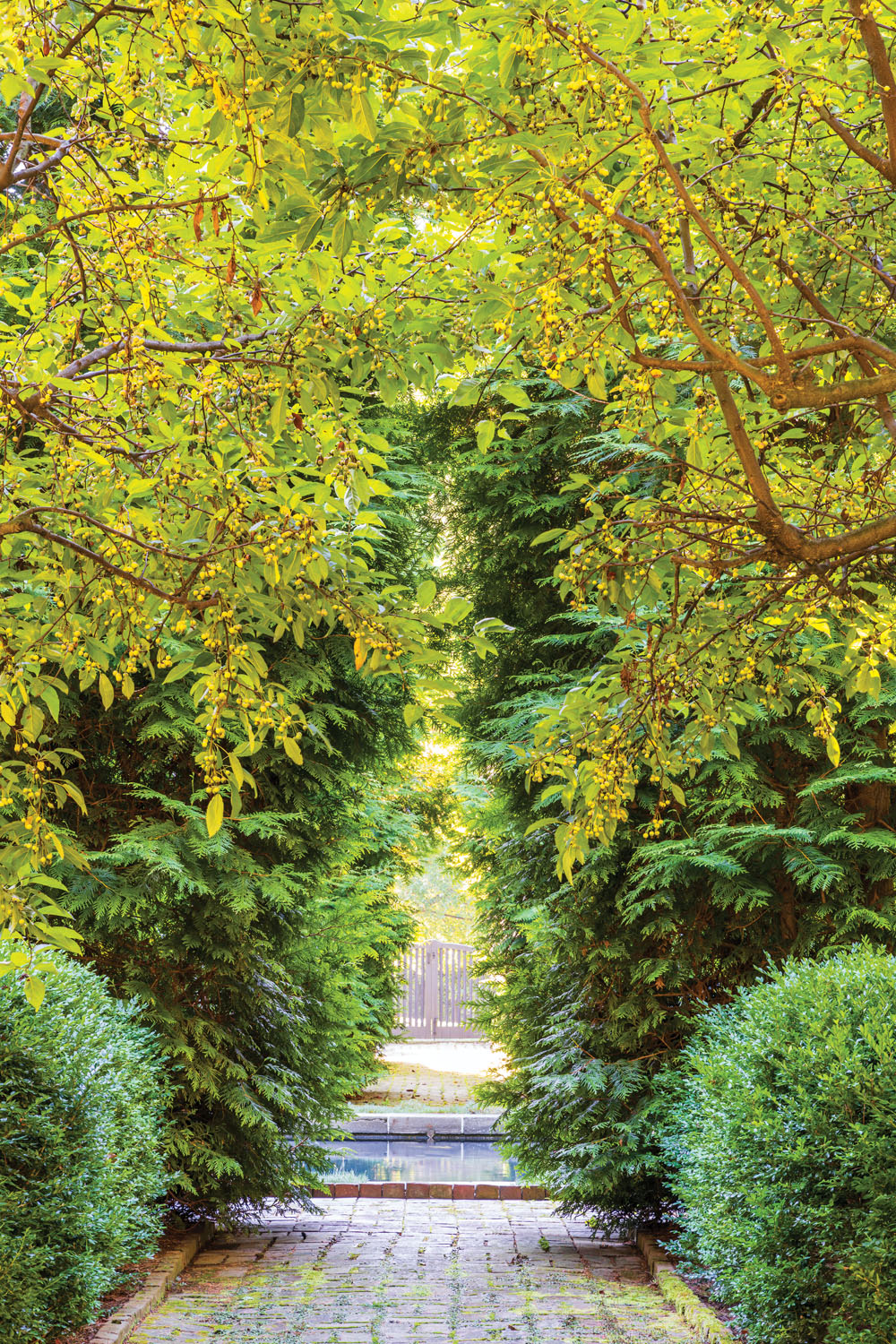

The 90-foot-long pond below the Upper Terrace had to be hand-dug during Chuck Woodward’s intense garden restoration. A thick patch of ‘Sunny’ Knock Out roses enhances the water’s edge, while a hardy border of lilyturf lines the brick walk.

“The gardens had been totally neglected, so we realized the task could not be accomplished quickly,” says Chuck, who explains that almost all of the boxwoods and dogwoods had been removed and the most prominent water features were no longer in existence. “Even the Long Pond had been covered in flagstone,” he says. “Reclamation was painstaking work because we had to be careful not to destroy original walls and stone enclosures that were laid over 100 years ago.”

‘Sunny’ is a hardy, showy Knock Out rose with a bright-yellow center that fades to creamy white.

The green foliage of Itoh peonies, Agastache ‘Blue Fortune,’ Iris sibirica ‘Caesar’s Brother,’ and Calamintha ‘White Cloud’ flanks the steps to a dining terrace and patiently awaits springtime’s season of blooms.

Twenty-two years later, Chuck’s wife, Anna, further refined the project. “Anna reworked the original outdoor rooms with a fine-tooth comb,” says Chuck. “She made them feel airy and put a lot of polish on them.”

To accomplish this, Anna worked with Krisheim’s head gardener, Nina Schneider, and her team, vetting plant materials with a keen eye. “This was necessary because some of the original plants were obsolete,” Anna says. “We also replaced 200 Buxus ‘Green Velvet’ boxwoods to reestablish original hedging in the walled garden.”

A private corner of the Upper Terrace features stone stairs that seem to lead nowhere but were once used by gardeners to access tool storage in a concealed shed over the wall. A stone bench beneath a carved wall plaque invites rest, in keeping with Frederick Law Olmsted’s penchant for “quiet spaces.”

Thorny, overgrown pyracantha espaliers were replaced with swaths of Knock Out roses planted for their lengthy floral display. The Annabelle Walk, lined with hydrangeas, became a charming introduction to the Summer House, and waxy white franklinia was added for its showstopping beauty. As Nina says, “Throughout the process, we kept the Olmsted brothers’ mantra in mind: This was never intended as a flower garden but rather as an architecturally landscaped garden.”

As the gardens were refreshed, the house also underwent a restoration, five years in the making. Upon completion, the monumental project, orchestrated by John Milner Architects, won the prestigious Grand Jury Award from the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia.

A wider view of the Upper Terrace

“Awards or not, what it all really means is that this house and its gardens have been—and always will be—an important part of our family’s heritage,” says Chuck. “I would never pretend to accomplish anything like my forebears did, but I feel I have now done my part. Krisheim will remain an important part of the story of Chestnut Hill for a long time.”

Note: 2022 marks the bicentennial of the birth of Frederick Law Olmsted. Learn more at olmsted.org

By Marion Laffey Fox | Photography by Rob Cardillo

This story appears in Flower magazine’s November/December 2021 issue, available on newsstands November 2. Subscribe, find a store near you, or sign up for our free e-newsletter.