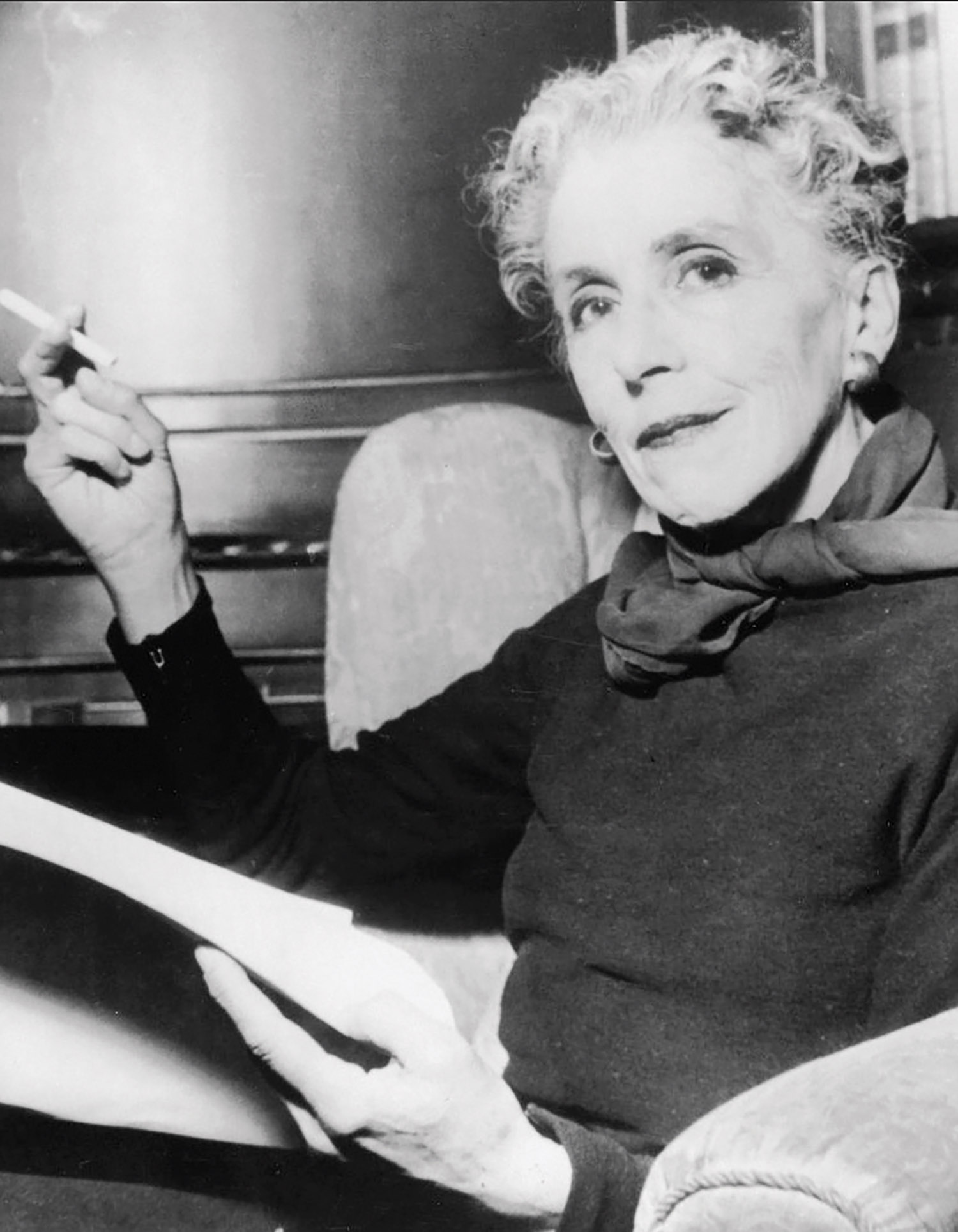

Photo by Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Portrait of the Danish author in the 1950’s reading in one of the wood-paneled rooms at Rungstedlund.

When one thinks of Karen Blixen, whose book Out of Africa memorialized her years as an expatriate in British East Africa, flowers do not immediately come to mind. And yet flowers, and the art of arranging them, were essential to her identity. While Blixen’s African residency lasted 17 years, the rest of her life, both before and after her time in Africa, was spent at Rungstedlund, her family’s manor house north of Copenhagen—and it was there that her devotion to flowers bloomed.

Blixen returned to Denmark in 1931 following the financial collapse of her coffee farm and a plane crash that killed her lover, Denys Finch Hatton. Upon her retreat to Rungstedlund, she spent her days arranging flowers from her garden and writing on her portable Corona No. 3 typewriter. For three decades, she pursued both interests with intensity. While some of her early short stories, poems, and other unpublished works reside in the Royal Danish Library, it was her first two books, Seven Gothic Tales and Out of Africa, that launched her writing career under the nom de plume Isak Dinesen.

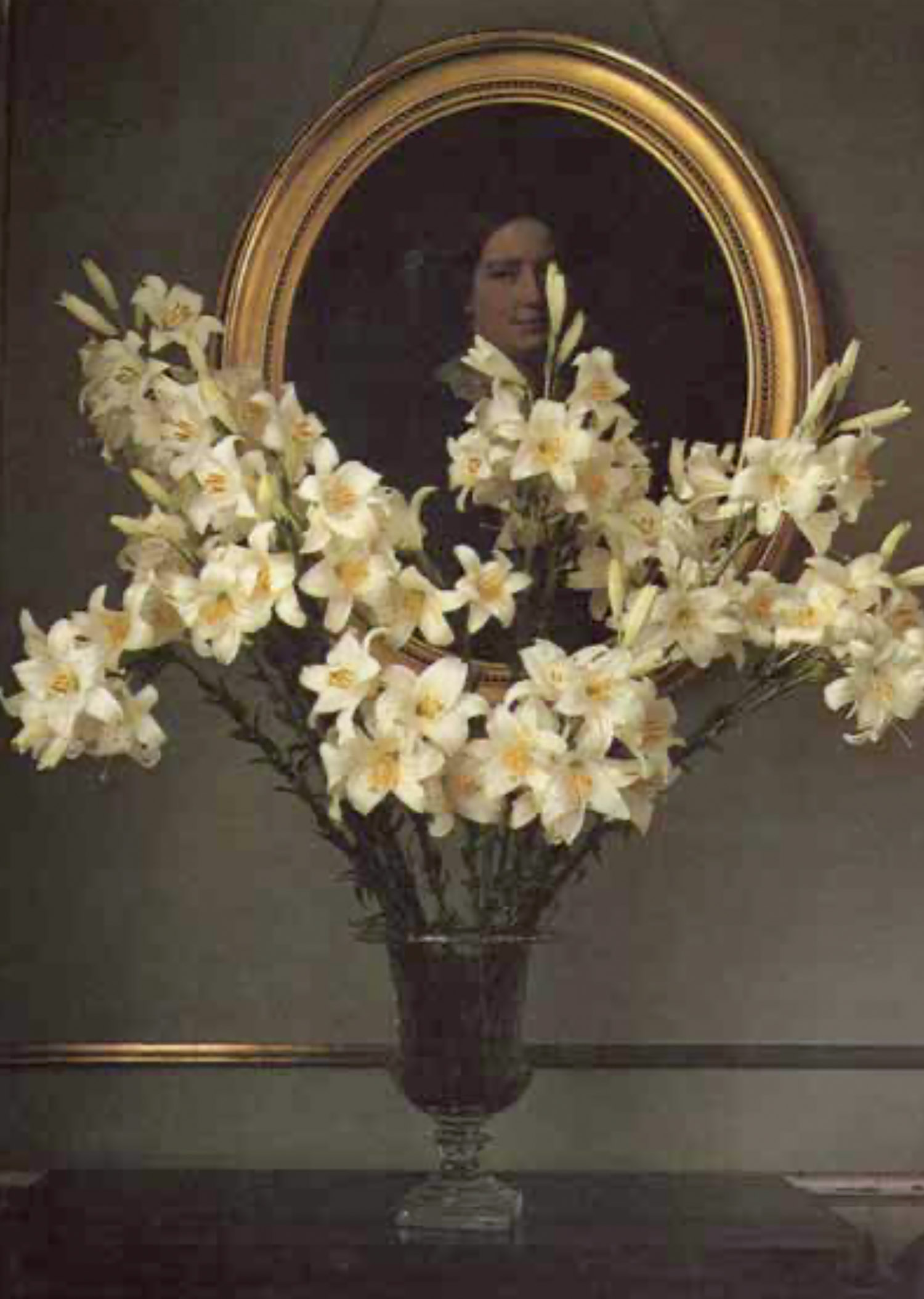

Photo by Karen Blixen from Karen Blixen’s Flowers, Nature, and Art at Rungstedlund. Christian Eilers Publishers 1992

Whether creating single-flower or composed arrangements, Blixen preferred a style that was loose and natural, just like the herbaceous borders from which they were plucked.

Blixen always had a creative mindset, originally wanting to be a painter. However, once she was back at home in Denmark, she began to channel her artistry into her flowers. Regarding her love for arranging, she once said, “Every time it is as if you were painting a flower picture.” When she was searching for the exact hue that might be lacking in an arrangement, she was known to hop on her bicycle to scour roadsides or turn up unannounced at the gardens of friends to see if she might find the precise shade needed.

The range of Blixen’s floral artistry was great, from creations consisting of just one type of flower to mad celebrations of color, scale, and texture. And much like well-known British florist Constance Spry, Blixen often employed cabbage leaves, leek foliage, and contributions from the side of the road in her arrangements. But her work was not imitative; it possessed a pathos that seemed to signal how tragically brief moments of true beauty are, perhaps born of her own difficulties. Among the most magnificent of Blixen’s floral works, which have been preserved for us through photographs, are richly nuanced monochrome arrangements. One such creation includes pristine white tulips, denuded of leaves, that seem to pirouette like slender-legged ballerinas. Set in a delicate opaline vase and placed in front of a pale blue wall, the arrangement calls to mind the restrained boldness of a Balenciaga silhouette. There also is a glorious masterpiece of all-white flowers—roses, Astrantia, ground elder, hostas, and marguerites—but with subtle variations of the hues (whites with hints of pink or lilac or yellow) that create a painterly effect.

Photo by Ole Jensen, Getty Images

A classic Danish farmhouse, Rungstedlund is now a museum. The rooms on the lower floors are furnished as they were on the day Blixen died. The upper floor is a gallery/exhibition space.

The range of Blixen’s floral artistry was great, from creations consisting of just one type of flower to mad celebrations of color, scale, and texture. And much like well-known British florist Constance Spry, Blixen often employed cabbage leaves, leek foliage, and contributions from the side of the road in her arrangements. But her work was not imitative; it possessed a pathos that seemed to signal how tragically brief moments of true beauty are, perhaps born of her own difficulties. Among the most magnificent of Blixen’s floral works, which have been preserved for us through photographs, are richly nuanced monochrome arrangements. One such creation includes pristine white tulips, denuded of leaves, that seem to pirouette like slender-legged ballerinas. Set in a delicate opaline vase and placed in front of a pale blue wall, the arrangement calls to mind the restrained boldness of a Balenciaga silhouette. There also is a glorious masterpiece of all-white flowers—roses, Astrantia, ground elder, hostas, and marguerites—but with subtle variations of the hues (whites with hints of pink or lilac or yellow) that create a painterly effect.

“I think that flowers themselves are one of the miracles of life, and that it is wonderful in every way to occupy oneself with them, but you will know that I have a special passion for arranging them. Every time it is as if you were painting a flower picture.”

—Karen Blixen

Blixen suffered physical ailments for most of her life, which limited her mobility and social life. Because of that, entertaining at home was vital to her. When expecting guests, she would often go into the garden very early in the morning in her nightdress and a pair of Wellies to pick armloads of flowers. After dropping them into buckets of water, she would head back to bed for a while. Then, to enchant her visitors, Blixen would festoon every room in the house with extravagant displays. At times, she would devote two or more days to her floral presentations.

Photo by Karen Blixen from Karen Blixen’s Flowers, Nature, and Art at Rungstedlund. Christian Eilers Publishers 1992

This haphazard arrangement of tulips makes it clear that Blixen was not a self-conscious flower arranger.

Photo courtesy of Charlotte Moss

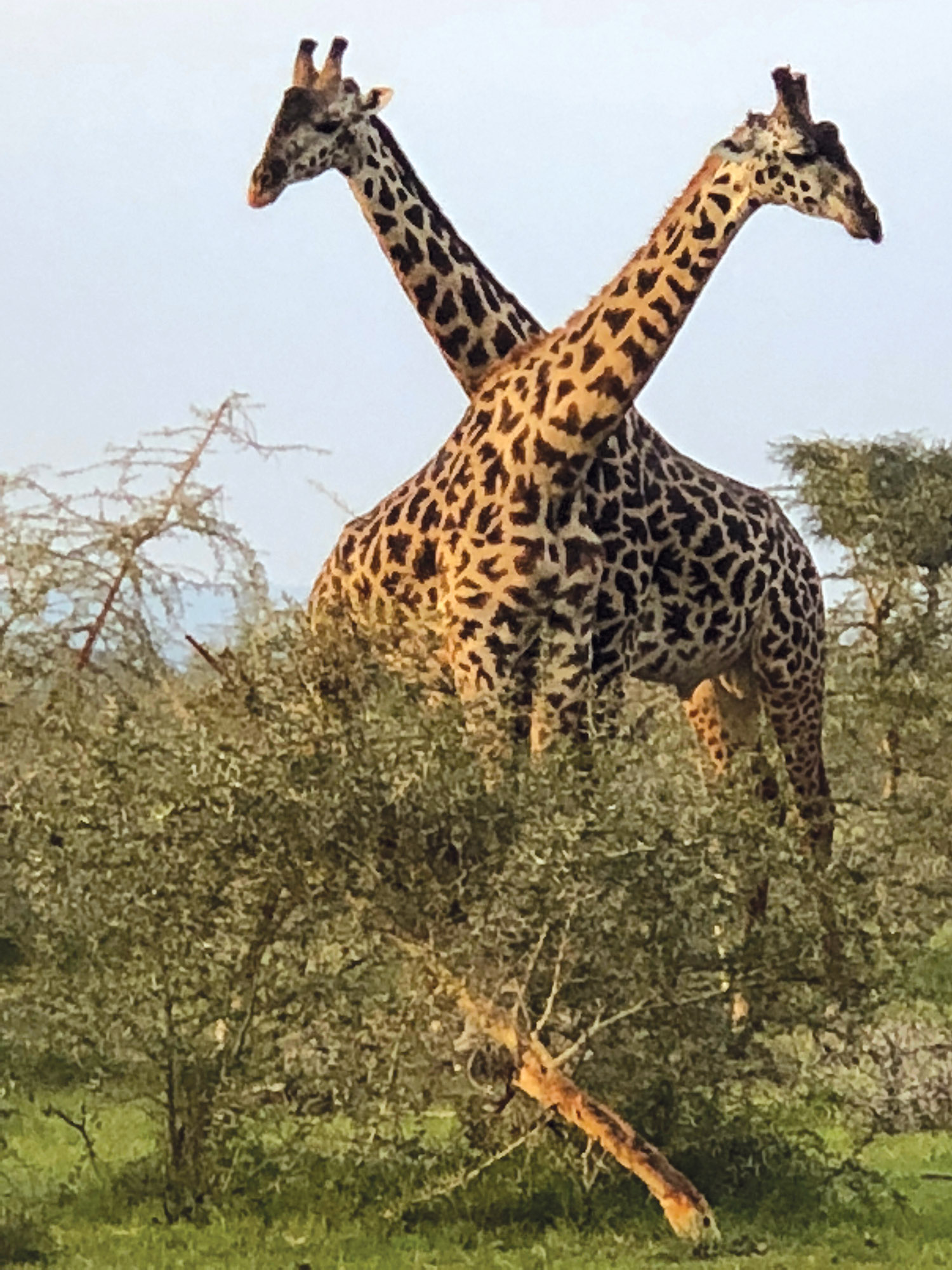

Blixen once said, “I had time after time watched the progression across the plain of the Giraffe, in their queer, inimitable, vegetative gracefulness, as if it were not a herd of animals but a family of rare, long-stemmed, speckled gigantic flowers slowly advancing.”

This crafting of flowers into arrangements of great magnificence and originality was in keeping with Blixen’s crafting of her own persona as grand and eccentric—she was known to eat only oysters and grapes and drink only Champagne. Flowers were a way for her, as a person known to be rather di fficult, to connect with people. Her arrangements were offerings of beauty and generosity to those who came to see her. So in touch was Blixen with her natural surroundings that her home while she lived in Africa, located in the Ngong Hills, was called Mbogani, meaning “house in the woods.” Rungstedlund includes plenty of woods as well, and it is there where Blixen is appropriately buried under the protection of an old beech tree.

By Charlotte Moss

Photo courtesy of Charlotte Moss

With a lifelong love of gardening, designer Charlotte Moss has long been intrigued with what draws people—especially women—into the world of horticulture. Some have made it their professions, while others have become enthusiasts, patrons, philanthropists, or simply weekend hobbyists. And then there are those who write about all things gardening. In her new column for FLOWER, Charlotte explores some of these women and the journeys that led to their passions for plants and flowers. She also has a forthcoming book with Rizzoli on the subject of gardening women set to release spring 2025.