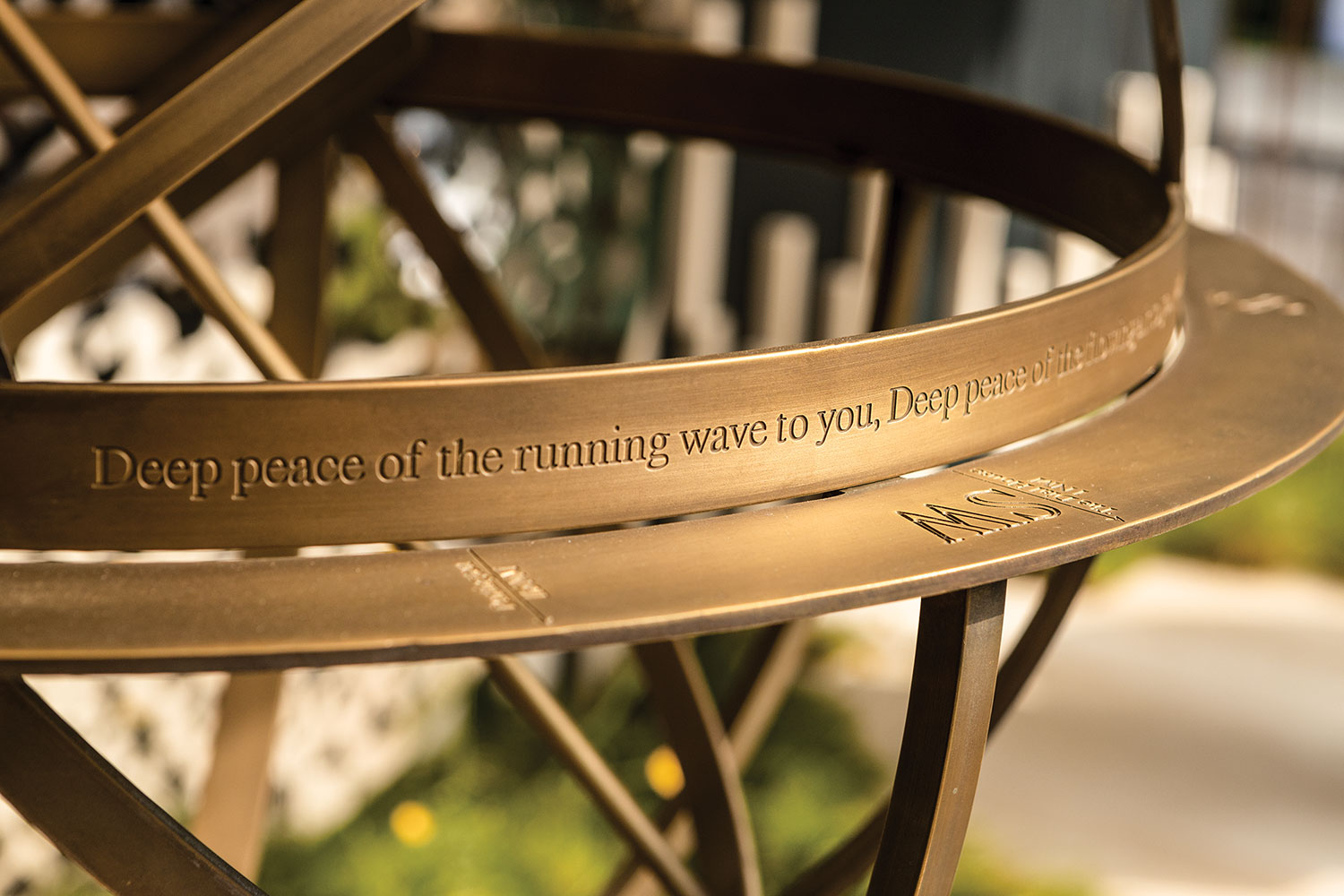

The Armillary Sphere, one of David Harber’s earliest and most appreciated works, is enjoyed in gardens throughout the world. The artist calculates each one to a specific location, in this case Pettifers garden in Oxfordshire, making it a highly accurate time piece. Photo by Clive Nichols

For more than a quarter-century, David Harber has been creating striking sundials, sculptures, and water features, gaining wide recognition and an international clientele. None of this seemed likely when he began. “It started with a sort of obsession, a passion for armillary spheres,” he recalls. “I saw one for the first time—a badly made one—and by the end of the day, I’d bought a book on how to make sundials, got some metal, and found an ideal example in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford.”

The sculptor in his studio at work on a fire chalice, which combines water circulating in an outer bowl with flames at the center.

In retrospect, most of his past pursuits had prepared him for this one: crafting form and structure while working as a potter and a thatcher, learning to cut and weld metal while converting a 160-foot steel barge into a performing arts venue (then spending 10 years plying Europe’s waterways with this Felliniesque floating theater).

Less obvious, but equally relevant, was his experience teaching rock climbing, which led to a job on an expedition in Patagonia as a mountaineering cameraman—those ventures proved he could leap into an abyss. “I wasn’t a mountaineer and was a very bad cameraman,” Harber admits, “just as I knew nothing about boats or theater when I bought the barge.”

In Volante, water flows down a recessed, mirror-polished, stainless steel vertical rill flanked by wings of verdigris bronze. The Art Deco-inspired water feature works equally well indoors. Photo by Clive Nichols

Photo by Clive Nichols

Inspired by a rippling field of ripening wheat, Quiver‘s mirror-polished leaves, set on elegant stems of patinated oxidized steel, form a cluster of reflected images that shift gently with every breath of wind.

Fortune may indeed favor the brave. When he made his first armillary sphere, Harber recalls, “I was down to my last £30, not a good place to be with a 2-year-old daughter.” Happily, he sold the piece at an art fair to actor Jeremy Irons, “and I was up and running,” he says.

Years later, Harber learned that his compulsion to create the sphere had ancestral roots—he’s a direct descendant of famed Elizabethan mathematician John Blagrave, who lived just a few miles from the sculptor’s Oxfordshire studio and workshop. An ancient device that tracked celestial events, the armillary sphere “was the computer of its day, the epitome of man’s understanding of the heavens,” Harber explains. The one he produced from an unrealized design by Blagrave is a prized possession—a true family heirloom.

Extraordinary shadows and illuminations of the immediate environment are reflected in the interplay of the stainless steel exterior and painted interior of the Filium sphere.

Initially, Harber created sundials. Calibrated to its precise location, a sundial is a site-specific marriage of art and science. “But that’s true of our sculptural pieces as well,” he says. “All our work is made to order. For each one, we talk to the client about tailoring it to the site and how to personalize it.” Clients can specify a version of an existing sculpture or commission a bespoke one, choosing the size, materials, and finish. “We use materials that last,” he says. “We expect these pieces to hold up for hundreds of years.”

Photo courtesy of David Harber

Inspired by the pencil pines of the Mediterranean, Quill stands like a tall, silent sentinel in the landscape. The delicate lattice of bronze petals are verdigris on the exterior and gilded with 23¾-carat gold leaf on the interior. At night, an LED bulb inside creates a lantern effect.

Aeon evokes the form of an Evil Eye, a symbol often referenced in Middle Eastern culture. Harber designed the massive verdigris bronze sculpture for RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2018. Photo by Clive Nichols

Harber’s 30-person team—including metalworkers, pattern makers, engravers, etchers, and waterworks and lighting technicians—allows him to tackle large, one-off sculptures, such as the enormous pendulum in the Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, airport that continuously marks the time. “It links heaven and earth and embodies Jeddah as the main gateway to Mecca,” he says.

In another instance, designs for a simple millennial sundial morphed into a monumental installation over the course of a two-hour pub lunch. The result was a circle of massive standing stones echoing Stonehenge.

The hemispherical David Harber sculpture, Sky Planet, is made from black puddle stones, with a core stone “kernel” and a mirror-polished stainless steel top to reflect the sky.

Any of Harber’s work can be personalized with an engraved inscription—names, dates, commemorative words, or sentiments like the phrase on one of his garden sculptures: “All the flowers of all the tomorrows are in the seeds of today.” A sundial or armillary sphere may include an arrow showing direction and distance to a place of importance, such as, for one English client, his native village in India. Works can also be oriented so the sun marks milestones, from equinoxes to anniversaries.

Echoing the shapes of the rounded shrubs, a spherical sculpture creates a play of solid and void.

Harber’s Falling Leaf in the Savills and David Harber Garden at the Chelsea Flower Show.

At the hyper-competitive Chelsea Flower Show, Harber’s installations have repeatedly won Best in Show awards (see his 2019 installation). His work can be found in private gardens, public spaces, and corporate settings all over the globe. “Forty percent of our work goes overseas, much of it to America,” he says. Today the sculptor is excited about the power of the computer to create intricate patterns and the way LEDs allow for playing with color, reflection, and shadow in new ways. What counts most, he adds, is whether a work meets the client’s needs: “It could be a simple armillary sphere that someone saved years for. That’s as satisfying for me as a 20-ton sculpture for a marina in Singapore.”

Studio visitors are welcome by appointment, davidharber.com.

Click the arrows (or swipe if on a mobile device) to see more

By Jeff Book