How many times have I crossed the Place Colette while walking from the St. Honore to the Palais-Royal in Paris? More than I can count. Place Colette, named for Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, is only a short walk from where the well-known writer spent most of her life near the gardens of the Palais-Royal. In fact, the famous restaurant Le Grand Véfour placed a plaque in her memory on her favorite banquette. One can imagine her dining there with friends such as Claude Debussy, Jean Cocteau, and Anna de Noailles.

It was Colette’s only daughter, Colette de Jouvenel, who lobbied for Place Colette to be named after her mother. André Malraux, the first Minister of French Cultural Affairs and a novelist himself, responded to her request and ensured that Colette was honored in this way. Malraux was also known for responding to the pleas of Jacqueline Kennedy regarding permission for the Mona Lisa to be exhibited in the U.S., one of the few times the painting has ever left France.

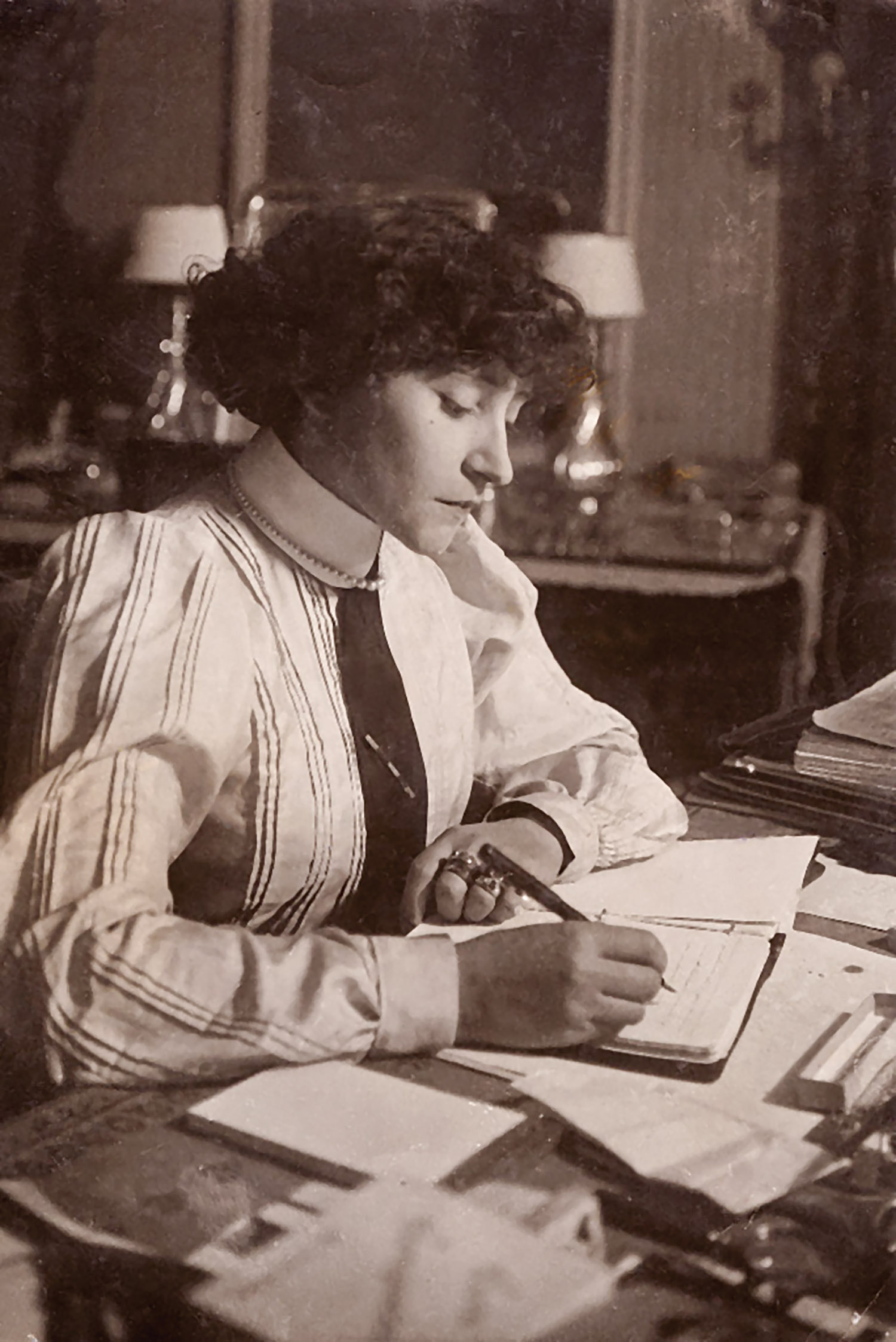

Colette as a young married woman and writer, describing life of the fin de siecle as she saw it.

Les Jardins de Colette, a contemporary flower garden, was created in memory of Colette. It is located in the town of Varetz near Chateau de Castel Novel where Colette often spent holidays. The garden covers over 12 acres and represents the phases of Colette’s life.

A literary life force best known for writing about the coming of age of adolescent girls in books such as Gigi, Claudine, and Chéri, Colette was not a gardener per se. However, the imagery evoked by her descriptions of gardens and flowers defies any lack of familiarity. Always lingering in her dreams was the memory of the roses and the grapevines in the bucolic Burgundy where she was raised. Later, when Colette referred to the house she purchased in Saint Tropez, known as La Treille Muscat, she proclaimed, “There is … a house, but that counts less.” For her, the focus was the garden she planned there that was to include roses, tomatoes, and herbs such as mint and tarragon. And while that idea of a garden never became a reality, in Colette’s world of fiction, it was real, tangible, and fragrant. Matthew Ward, translator of Colette’s book titled Flowers and Fruit, described her writing as “an attempt to turn botany text into poetry.”

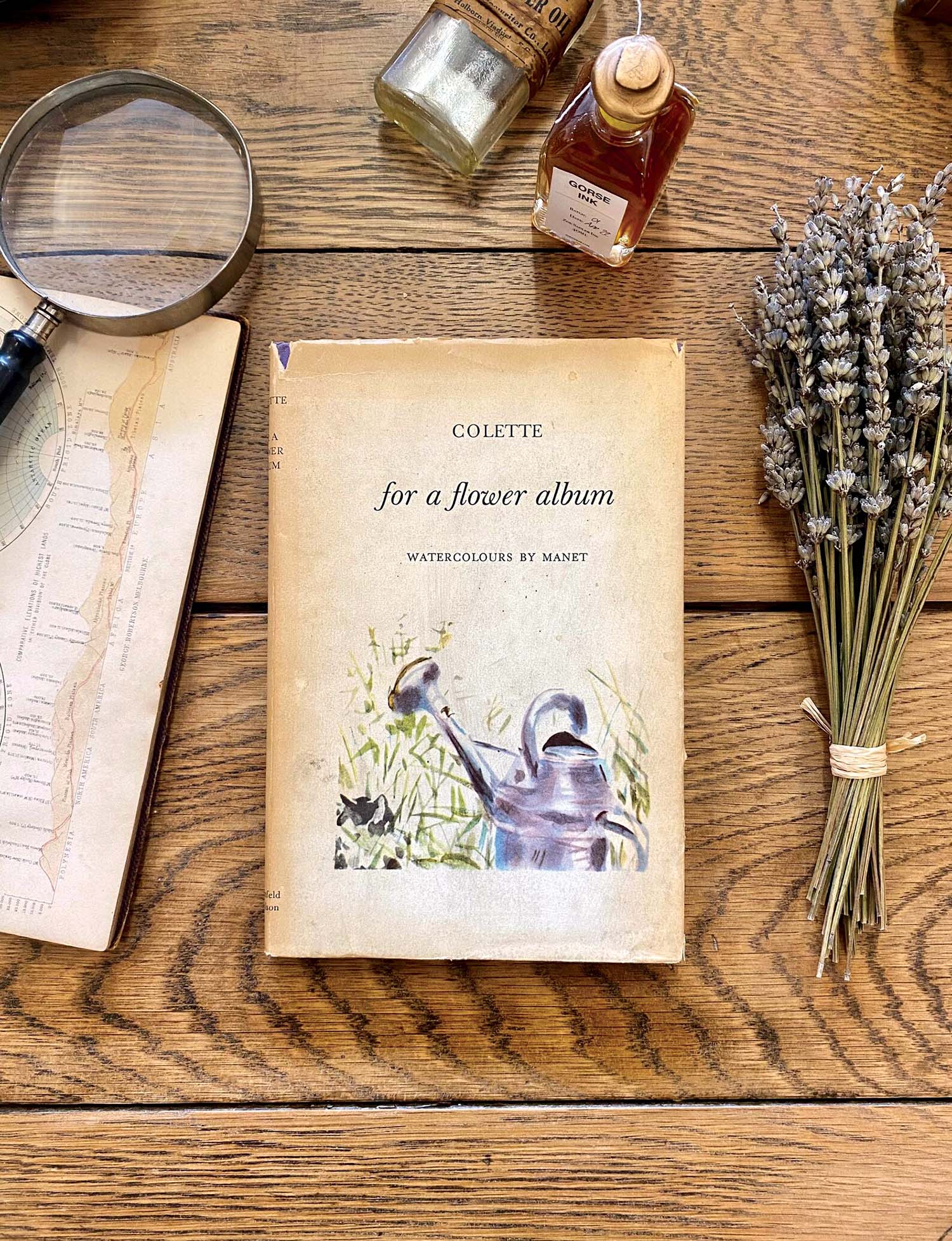

While most of Colette’s works had abundant references to flowers, one book in particular, For a Flower Album, broached the subject on a deeper level. A volume translated by Roger Senhouse and illustrated with watercolors by Manet, it was the smallest collection of her writing but included her love letters to and about flowers. Ironically, the book was not published until 1959, five years after Colette’s death. It was just one of over 80 works of fiction and dramas that made up her prodigious career, while her correspondence reportedly fills even more volumes. As Australian writer and intellectual Germaine Greer once said, “The precious moments for Colette were not those of full flush, but the budding and fading, full of promise or regret.”

From her entresol apartment, Colette viewed the Palais-Royal through a forest of pleached lindens, almost defying the fact that she was in the heart of Paris.

Colette’s writings, many of which were based on her life and certain family members, were viewed as controversial by some. As a result, the Catholic Church denied her a religious funeral, and Colette became the first and only French woman to have a state funeral. Fellow writer Graham Greene protested the church’s refusal to no avail. Yet more than 6,000 mourners turned out as a show of respect for the novelist, journalist, actress, mime, and raconteur. In Père Lachaise cemetery, her final resting place, Colette can be found amongst other writers, poets, and artists, including two that she admired most, Marcel Proust and Honoré de Balzac.

Pink "Colette" roses flowering in Les Jardins de Colette.

In For a Flower Album, Colette proclaimed, “There is no denying that flowers are my delight.”

At the end of her life, Colette spent her days on a divan under a fur throw in her Palais-Royal apartment. Incapacitated by arthritis—and with her Parker Duofold poised over her signature blue paper and a vase of roses on her desk— she was to write until she could no longer. The last word she uttered, regarde, was fitting as it was the way she lived her life—looking, feeling, wondering, accepting, and living.

With a lifelong love of gardening, designer Charlotte Moss has long been intrigued with what draws people—especially women—into the world of horticulture. Some have made it their professions, while others have become enthusiasts, patrons, philanthropists, or simply weekend hobbyists. And then there are those who write about all things gardening. In her new column for FLOWER, Charlotte explores some of these women and the journeys that led to their passions for plants and flowers. She also has a forthcoming book with Rizzoli on the subject of gardening women set to release spring 2025.

MORE WOMEN IN HORTICULTURE

-

- Nancy Lancaster: Haute and Humble

- Lee Miller and Farleys House Garden

- Empress Joséphine’s Gardens at Château de Malmaison

- Melissa Gerstle Strikes the Balance

- Andrea Filippone at Jardin de Buis

- Nicole de Vésian Garden at La Louve

- Chatsworth House and Garden and the Duchess of Devonshire

- Anne Spencer: Garden as Muse