A portrait of the Duchess by Mogens Tvede from 1949 when she was the Marchioness of Hartington and living at Edensor House on the Chatsworth estate.

I first visited England’s Chatsworth in the early 90s with the American Friends of the Georgian Group. We toured the house, walked the gardens, and had lunch in the family dining room with Andrew Cavendish (then Duke of Devonshire) and the charismatic Duchess Deborah (“Debo,” as she was known to friends). I remember the beautiful table setting, the tall Chinese screen from which the waiters emerged, and the commanding portrait of Henry VIII looking over us. But I also remember seeing a dog bed and large bag of dog food under the gilded William Kent console.

To experience this extraordinary place in such a personal manner, to have history interlaced with personal anecdotes, makes the bricks and mortar come alive and leaves you wondering what tales the 200-year-old trees there could tell.

Chatsworth was built by the indomitable Bess of Hardwick, the wealthiest and most powerful woman in Elizabethan England next to the Queen. Upon marrying her fourth husband (the Earl of Shrewsbury and the wealthiest man in England), Bess set about building one of the greatest treasure-filled houses in Britain. Through subsequent generations, Chatsworth became the home of the Cavendish family. The Duchess was a mere 30 years old when she and Andrew assumed ownership upon the death of Andrew’s father. His older brother, the heir apparent, had been killed in World War II, leaving Andrew as the next in line to assume the enormous responsibility of stewardship of Chatsworth, a role he and the Duchess performed handsomely for 54 years. Debo, the youngest of the often celebrated and occasionally scandalous Mitford sisters, took her new responsibilities seriously, making Chatsworth and its gardens one of the most successful English Country estates today.

Photo by Christopher Furlong

Imagine the task of being the chatelaine of a property with these stats:

- 273 rooms

- 24 baths

- 7,873 windowpanes

- 17 staircases

- 3,426 passages

- 359 doors

- 1.3 acres of roof

- 40,000 acres of land, with 105 acres devoted to the gardens

As we continued our tour in the garden, we listened to the Duchess explain to the American architect Hugh Newell Jacobsen that the trees destroyed in the brutal storm of 1987, which devastated parts of Britain and France, “will soon be replanted for others to enjoy in 200 years’ time, just as we have enjoyed them.” In her own metaphorical terms, “ … the battle with nature, which is gardening,” was tragically in evidence here. I will never forget listening to her explain this to Hugh and the impact it had on me. It was a testament to her far-reaching vision and understanding of the responsibility incumbent upon her and the Duke to secure the future of the Cavendish family home and its grounds as an important historical monument in Britain.

The Duchess, pictured here with Hugh Newell Jacobsen, pointing out where a new allee of trees would be planted.

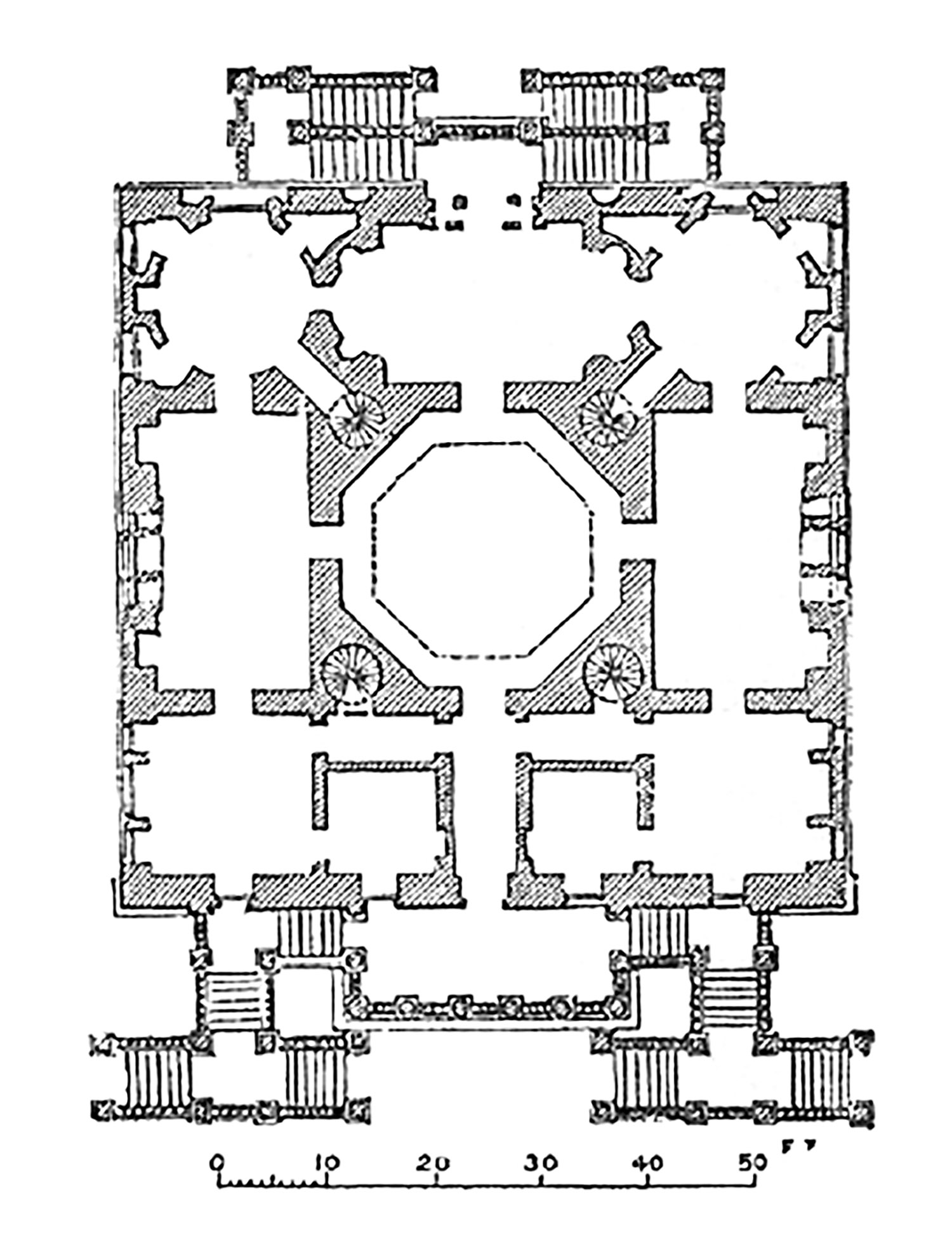

In the garden on the West Lawn, golden boxwoods form a replica of the floor plan of Chiswick House.

In the garden on the West Lawn, golden boxwoods form a replica of the floor plan of Chiswick House.

The Duchess with a couple of the family dogs.